Our work

The

First Years

Light and

Colours

Stereoscopic work

Technical developments and new

visions

ViewPoints

From our

Viewpoint

The First Years

We started working

together in 1968 while still at art school. Our work from this period and

also that which we showed at our first exhibition in Iceland owed much

to our experiments with optical colour mixing – the mixing of colours as

light. Perhaps the one person who inspired us most when we were embarking

on our career as artists was Sydney Harry (1912-1991) who used to come over to

Bath Academy two or three times a year to hold unforgettable lectures on colour phenomena.

Sydney was then Senior Lecturer in colour and perception studies at Bradford College of Art

as well as being a fertile and sensitive artist. Sydney's experiments with colour mixing aroused our

special interest. He had done considerable research into the way that small areas of juxtaposed colour merge

and alter when viewed from a distance - as they do in woven textiles - and named the phenomenon "mobile colour".

Steve knew Sydney quite well and we exchanged letters and slides of our work for some time after we moved to Iceland.

While at Bath

Academy of Art, then situated at Corsham in Wiltshire, we participated in

several exhibitions. The first of these was Play Orbit,  an exhibition of toys by over 120 artists from all disciplines organized by the Institute of Contemporary

Arts, in 1969. Bath Academy and several other art schools were also invited to

send in entries. Margrét had by then moved to Brighton but we continued to work

together, making use of the facilities both at Corsham and Brighton College of Art.

The two of us and another Corsham student, Peter Juerges, constructed a giant

praxinoscope, an adaptation of a Victorian optical toy in which mirrors in a revolving drum produce the illusion

of movement from a strip of images. We took this process a stage further and used the praxinoscope to blend images by

persistence of vision. This led, amongst other things, to optical colour mixing

in static images. The drum, when rotated considerably faster than was necessary

for simple movement, produced strong secondary and tertiary colours from the

flicker of light primaries (red, green, blue).

an exhibition of toys by over 120 artists from all disciplines organized by the Institute of Contemporary

Arts, in 1969. Bath Academy and several other art schools were also invited to

send in entries. Margrét had by then moved to Brighton but we continued to work

together, making use of the facilities both at Corsham and Brighton College of Art.

The two of us and another Corsham student, Peter Juerges, constructed a giant

praxinoscope, an adaptation of a Victorian optical toy in which mirrors in a revolving drum produce the illusion

of movement from a strip of images. We took this process a stage further and used the praxinoscope to blend images by

persistence of vision. This led, amongst other things, to optical colour mixing

in static images. The drum, when rotated considerably faster than was necessary

for simple movement, produced strong secondary and tertiary colours from the

flicker of light primaries (red, green, blue).

The Play Orbit praxinoscope and five of its strips

|

The

Play Orbit praxinoscope

and five of its strips |

We

have always been interested in toys and made several colour-mixing toys while at

art school, one of which,‘Rollers’,

can be seen on our Gallery

page.

The following year we made several boxes for viewing coloured light phenomena. One of these used  three

greyscale colour separation films and angled glass plates to produce a composite colour image. Another used a similar principle with lights

and shutters to mix the colours on painted cards and a third used polaroid sheets on revolving disks to produce colours from transparent objects. These three

boxes were shown at the Whitechapel Art Gallery at an exhibition called COLOUR?

in early 1970. Other exhibits shown there included mobile colour work by Sydney Harry and several fluorescent strobe-lit 'Videorotors' by Peter Sedgley who also knew and was influenced by Sydney. Sydney also wrote an article in the catalogue about additive and subtractive colour mixing and mobile colour.

Soon afterwards a continuation of the Whitechapel COLOUR? show opened at the Graves Art Gallery in Sheffield. This included some new work that had not been shown previously and was a huge success with over 21 thousand visitors. The Leicestershire Collection bought the 3-dimensional 'Zig-Zag Reflecting Structure' which was amongst the work that we exhibited in Sheffield.

Margrét also held an exhibition of her work at Brighton Radio and in a broadcast interview she explained how the energy of Iceland, the land, the sea, the light and the weather influenced the forms and colours of her work.

>

three

greyscale colour separation films and angled glass plates to produce a composite colour image. Another used a similar principle with lights

and shutters to mix the colours on painted cards and a third used polaroid sheets on revolving disks to produce colours from transparent objects. These three

boxes were shown at the Whitechapel Art Gallery at an exhibition called COLOUR?

in early 1970. Other exhibits shown there included mobile colour work by Sydney Harry and several fluorescent strobe-lit 'Videorotors' by Peter Sedgley who also knew and was influenced by Sydney. Sydney also wrote an article in the catalogue about additive and subtractive colour mixing and mobile colour.

Soon afterwards a continuation of the Whitechapel COLOUR? show opened at the Graves Art Gallery in Sheffield. This included some new work that had not been shown previously and was a huge success with over 21 thousand visitors. The Leicestershire Collection bought the 3-dimensional 'Zig-Zag Reflecting Structure' which was amongst the work that we exhibited in Sheffield.

Margrét also held an exhibition of her work at Brighton Radio and in a broadcast interview she explained how the energy of Iceland, the land, the sea, the light and the weather influenced the forms and colours of her work.

>

While we were still at art school we were introduced to the late Cyril Barrett (1925-2004) who was then professor of Philosophy at the University of Warwick in Coventry and exchanged letters with him. He wrote several books on art and had recently published the book 'Op Art' (Studio Vista, London, 1970). While he was writing the book, Sydney Harry had lent him his unpublished research into optical colour mixture. Cyril Barret was impressed by what we were doing and wrote an introduction for our 1972 exhibition 'Light and Colours'.

In the autumn of 1970 we moved to Iceland and continued to experiment and develop our work with colour. It soon became apparent to us that a truly living and vibrant optical colour mixture could only be achieved by using very small areas of colour. This in turn neccessitated a switch from a two-dimensional surface to a three-dimensional structure. As early as 1969 we had made a small three-dimensional work 'Perspex 1' that changes colour. We frequently opted for the use of stripes of light primaries partially blocked by black or neutrally coloured strings. When strongly lit by a concentrated light source the strings also produce shadows on the striped relief. Colours and forms appear to glow and shift as the spectator moves in front of the work. Colours become disconnected from the surface and live an independent life in the space between the surface and the viewer.

Light and Colours

Here follow some

excerpts from the catalogue of our first exhibition together on in Iceland, ‘Light

and Colours’ (Ljós og litir), Nordic House, Reykjavík, December 1972.

Here follow some

excerpts from the catalogue of our first exhibition together on in Iceland, ‘Light

and Colours’ (Ljós og litir), Nordic House, Reykjavík, December 1972.

“... Our plan was to discover a method of producing a mobile, living colour such

as can not be achieved by the mere use of paints. The colours of the paint

factory are dead compared with the vibrant colours which occur in nature. Nature

builds up her colour range through the interaction of light upon microscopic

sub-structures. White light is diffracted and broken up into a frenzy of

vibrating colour. In using a fine structure of dots or stripes, we are emulating

nature’s method of producing colours by decomposing white light. ...”

“... The technique that we use is the outcome of extensive research into colour

phenomena ... and the interaction of colour and structure in two and three

dimensions ... which we started on while we were in England. It seems to owe

more to the optics textbook than the painter’s manual and, as far as we know,

it is unique. ...”

“... Movement has long been important in our work. Sometimes the works themselves

move, more often though, the movement is induced by the movement of the

spectator. We look upon this movement in terms of an added dimension, the

dimension of time. It is never possible to experience our work from a single

viewpoint. We like to play with the idea that there is always a new experience,

a new stimulus just round the corner, the unseen image is always waiting for us

and that it only becomes visible after a conscious effort on the part of the

beholder. Successive images give our works the same dimension as in a movie

film, except that the beholder can now have an element of control over what he

sees. Controlled participation of the spectator is a comparatively new

development in the visual arts resulting largely from the freeing of the image

from the picture plane. It will be interesting to see where this will lead. The

spectator and his impressions have now become part of the work, while the object

on the wall serves as little more than a generator of stimuli. ... ”

In our 1972 exhibition we used for example coloured lights, brushed aluminium or

chromed brass reflectors and painted glass to achieve colour and form changes.

We also found a method of heat-moulding painted perspex which we had not seen

used before.

“... The materials from which our works are constructed are meaningless in

themselves. We select (them) according to our requirements and are not concerned

with the question of whether we are making a sculpture or a painting. ... You

must look beyond the object on the wall – its construction is often difficult

and laborious since accuracy of structure is a prerequisite. Nor should you poke

your nose between the strings –the colours will only dazzle you. Instead,

stand back, open your eyes and be aware of the sensations.”

|

|

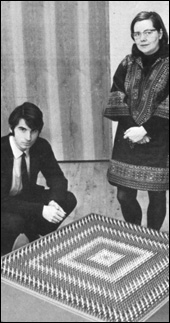

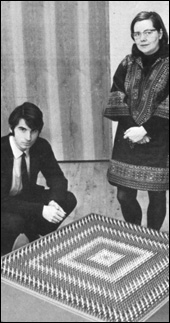

A

press photo of us from Light and Colours |

“There is nothing far-fetched about an art form that deals with pure sensation, for

what is music other than that? Our experience of the world is built up from the

stimuli, the sensations, that we receive from it; so why should we not express

the world around us – its sounds and smells as well as its colours – in

terms of the visual impulses which are associated with it? Our experience is

built up of a complex combination of sensory responses, ... so we consider it

insufficient to represent only what is seen by the eye.”

“By being less specific about place or time, by concentrating on sensations

including but not confined to the visual and by translating various kinds of

energy into a visible form one can maybe give a description of one’s subject

that is not possible by representational painting alone. This is not to say that

these works are always calculated to give a definite sensation. The elements of

chance and experiment are always there. The very instability of the colour

structure and the fact that the work is constantly on the move makes it

difficult to pre-determine the precise effect.”

“We have repeatedly noticed the relationship between our work and the work of the

Impressionists and that grandfather of Impressionism, Wiliam Turner. They have

all dealt with the analysis of colour and light stimuli. Their world they

represent is broken up, fragmented, until the picture surface is little more

than a mosaic of dabs of bright colour. At the same time pictorial depth is

reduced and our attention is brought to the surface ... . Our work takes this

theme a stage further. The patches of colour have now become very small and

completely regular which leads to dazzle and optical mixture. It becomes

increasingly difficult to fix the colours in space. They seem to hover somewhere

in front of the surface – changing and unstable.”

An article in Morgunblaðið, 8th December 1972:

"Don't miss going into the basement of the Nordic House these days. There you will see light and shadows take on new and exciting forms. With this exhibiton Margrét Jóelsdóttir and Stephen Fairbairn have started a new chapter in Icelandic art. This is the first exhibiton in Iceland solely dedicated to what some people call Op or Kinetic art. But, as one may read in their catalogue, Margrét and Steve don't like having their work classified, so I will respect their wishes and leave classification to others.

This exhibiton is comprised of 37 works, all proficiently and painstakingly made. Their workmanship is much to their credit and I imagine that it would not be possible to create pieces such as theirs without being in complete control of imaginative and precise techniques. …

… Margrét and Steve walk new paths in their research into light and colour. The result is entertaining and refreshing … and the exhibition is extremely well hung, so that the viewer can move around freely to see the work from different angles, allowing the colours and forms to change with the viewpoint. I am in no doubt that this show is an important event in the progress of our culture and Margrét and Steve are truly expanding the bounds of art in Iceland today. … Our cousins in Scandinavia would doubless say that this show bore a certain 'kultur' (culture), which is more than can be said of many other exhibitions that are presented to us here in Reykjavík. I hasten to encourage people to see this work and feel confident that we will see much more from this couple."

Hjörleifur Sigurðsson, Artist and Critic.

From the book ‘Aldarslód’ (Path of a Centuries) by the art historian Björn Th.

Björnsson, (Mál og menning, Reykjavík, 1980):

"... Margrét Jóelsdóttir and Stephen Fairbairn are practically the only

artists in this country (Iceland) to have worked with optical art. ... (Unlike

those who work with black and white geometrical patterns) their aim is not to

confuse visual messages but to produce forms and colours which change by

movement of the light source or of the beholder in front of the work. ... Such

pictures have no tactile surface as such but are rather stimulators for the

visual experience of movement".

At the time of the ‘Light and Colours’ exhibition Björn Th. Björnsson had a

weekly programme on the arts on the Icelandic television. He filmed some of our

work and took an interview with us shortly before the opening.

Stereoscopic work

In 1976 we became members of the Finnish group, Dimensio, which

was comprised of a number of artists involved largely with optical and kinetic

work. The group held a seminar at Hässelby Slot near Stockholm and

we showed some of our work there. Peter Sedgley was also a member of Dimensio but did not take part in the Hässelby seminar. The following year Dimensio held a touring

exhibition in Finland where we showed a folding stereoscope with a series of cards which we

named ‘Stereo Portfolio’. Over the years we have done quite a lot of experimental work with stereoscopic

images, using coloured glasses, mirrors, prisms, lenses and polarizing

filters to produce spatial effects. The main problem with exhibiting this kind

of work is the considerable number of people who cannot see stereoscopic images

properly, so we have not as yet embarked on a fully-fledged stereo exhibition.

Nor does this kind of work reproduce very satisfactorily on a website, so we

hope this picture will suffice to give an idea of what the ‘Stereo Portfolio’

looks like.

In 1976 we became members of the Finnish group, Dimensio, which

was comprised of a number of artists involved largely with optical and kinetic

work. The group held a seminar at Hässelby Slot near Stockholm and

we showed some of our work there. Peter Sedgley was also a member of Dimensio but did not take part in the Hässelby seminar. The following year Dimensio held a touring

exhibition in Finland where we showed a folding stereoscope with a series of cards which we

named ‘Stereo Portfolio’. Over the years we have done quite a lot of experimental work with stereoscopic

images, using coloured glasses, mirrors, prisms, lenses and polarizing

filters to produce spatial effects. The main problem with exhibiting this kind

of work is the considerable number of people who cannot see stereoscopic images

properly, so we have not as yet embarked on a fully-fledged stereo exhibition.

Nor does this kind of work reproduce very satisfactorily on a website, so we

hope this picture will suffice to give an idea of what the ‘Stereo Portfolio’

looks like.

Technical developments and new visions

Computer technology, which we were quick to adopt in the mid-eighties, facilitated our work to some extent and gave us freedom to explore new vistas. Digitalization also made working with colour much less laborious and opened new paths for experiment.

Of late nature has become more visible in our work but we still keep true to the basic premise of our art that mutability and the unseen image will only be perceived with the participation of the beholder. We have made much use of glass and mirrors to this end and often blend images using a very similar technique to that which we used in our colour-mixing boxes of the late 1960s. Two of our works using etched mirrors, 'Sun-Runes' and 'Eyes of the Ocean', were made for the exhibition 'Art in Energy Centres' which was held in the year 2000 in two hydro-electric power stations as the Society of Icelandic Artists' contribution to the millennium celebrations.

ViewPoints

In late 2001 we held a big show ‘ViewPoints’ (SjónarHorn) in the Kópavogur

Art Gallery (Greater Reykjavík Area).

Here follow some excerpts from the ViewPoints catalogue which was printed in Icelandic and

English. Adalsteinn Ingólfsson helped us with the introduction. He is a art historian, critic and journalist. Educated in the UK, he has written a

number of books on Icelandic art and artists. Articles by him are frequently to

be seen in English-language publications on Iceland and he writes reviews for

the Icelandic press.

In late 2001 we held a big show ‘ViewPoints’ (SjónarHorn) in the Kópavogur

Art Gallery (Greater Reykjavík Area).

Here follow some excerpts from the ViewPoints catalogue which was printed in Icelandic and

English. Adalsteinn Ingólfsson helped us with the introduction. He is a art historian, critic and journalist. Educated in the UK, he has written a

number of books on Icelandic art and artists. Articles by him are frequently to

be seen in English-language publications on Iceland and he writes reviews for

the Icelandic press.

Monuments to Mutability

“And time is like a picture,

that is painted of the water

and, in part, of me.”

(Steinn Steinarr –

Time and Water)

It is far from easy

for one who studies art to come to grips with an exhibition like the one which

Margrét Jóelsdóttir and Stephen Fairbairn are presently launching. This can

neither be ascribed to unclear aims of the exhibitors nor to a lack of

professionalism on their part. On the contrary, this husband-and-wife duo are

organized in their thinking and phenomenally skilful. The problem of the art

critic lies primarily in the fact that Margrét and Stephen interpret their own

sentiments and viewpoint with an insight and persuasion that makes further

explanations almost unnecessary.

These traits alone

give them a special place in the Icelandic art world, because as many people

know, reticence to discuss the content and origins of their work is a strong

characteristic of Icelandic artists.

The peculiarity of

this couple reaches further. Marriages between dissimilar artists are indeed

common, and the rule would appear to be that the more unlike the couples are in

their art, the more permanent their tie. But a close, long-term artistic

co-operation between couples is a rare thing, even in the big world. At present

I can only recall one other case where a couple have been as one person in an

artistic respect, and this case comes from the design sector. Here I refer to

the American designers Charles and Ray Eames.

The third surprise

comes in what might be called their ‘methodology’, coming as they do from

what might appear as very dissimilar backgrounds; Margrét is educated as a special teacher and artist and has worked in both these fields. Stephen is British-born and studied graphic design, a profession that

he has worked at for many years. They began their co-operation during their

student days in England.

To co-ordinate their

standpoint and present it through their art they have sought new methods from

far beyond the limits of tradition. For example they have made use of various

aspects of the ultra-modern. Works such as ‘Time-Tellers’

and ‘Places’

are a personal extension of the installation format that the youngest generation

of artists is preoccupied with. In the same way one might say that works like ‘Portable

Sunbeams’ and ‘Beach Comb’

have something in common with the work of the Fluxus artists. Quite unexpectedly

their work ‘Surf-Harp’,

a variation on the restless stones of the shore, calls to mind Jón Gunnar

Árnason’s ‘Cosmos’ installation. And finally one can find an echo of

experiments by some of the younger generation of concept artists to position

themselves in a new way in nature in a work that Margrét and Stephen simply

call ‘Places’.

But even though

Margrét and Stephen’s work may have various things in common with the work of

other modern artists, there are a number of aspects which make them unique. For

example the idea – the concept – is, for the latter, of greater importance than

the workmanship or final pictorial product. For Margrét and Stephen

high-quality workmanship is an inseparable part of the concept and ensures the

power of its influence.

Most interesting of

all is nevertheless how some of their ideas have called for a totally new form

of presentation. Here I refer for example to their nature-linked works such as ‘Sun-Runes’ and ‘Windows’.

These works have a built-in interaction and demand the direct participation of

the viewer in a predetermined process where mirrors play an important rôle. We

perceive “the constant movement of the sea”, “the interplay of sun and shadow“

or the fleetingness of all being, the fact that the same phenomenon can take on

a whole new appearance each time we cast eyes upon it. ... We look into these

boxes from many angles and in various lighting conditions and obtain a glimpse

of the magic of the moment.

From the very

beginning Margrét and Stephen have been very consistent in their objectives.

The optical string works that they made 30 years ago are also variations on the

theme of change and the moment. They changed constantly before the beholder,

depending on his viewpoint and the direction of the light. And even today their

works are characterized by a variation of these strings. Sometimes strips of

mirror remind us of strings that play the music of the sea. Another kind of

music comes from the dancing sun mirrors in ‘Sun-Runes’.

‘Portable Sunbeams’ play a kind of musical

optimism on seven vertical mirrors/strings and in the work ‘Passing’ vertical stakes/strings produce a

syncopated rhythm, an accompaniment to time.

Without wishing to

make too much of the part played by strings in Margrét and Stephen’s work I

should finally like to mention the energy strings that form the clockwork of

their ‘Surf-Harp’, and the rake which they use

to alter a beach into strings for the waves to play on in their work ‘Beach-Comb’. Can one be surprised that they

themselves see an extension of themselves, a human form, in these long, thin

shapes?

Whence did Margrét

and Stephen get this longing to halt the process of time? They have themselves

named the deep-rooted influence of the sea and the shore. In Ísafjördur, where

Margrét was brought up, the sea was often rough, “pebbles were hurled over the

wall, waves beat the house and seaweed was blown onto the road behind.” In

Milford, Stephen’s childhood home, there were often floods in the winter, gales

shook the house and the windows became caked with salt. The rhythm of the sea

is thus engraved into their consciousness.

Margrét and

Stephen’s endeavour to ‘organize the erratic’ is therefore partly a longing for

stability and a refuge in creation. A prerequisite for this longing is

self-knowledge, man’s understanding that he is himself part of the mutability

of the whole. They emphasize this again and again with many kinds of

reflection. To begin with one can view the mirrors as a kind of alias for the

artists themselves, a prerequisite of artistic self-knowledge. “Here was I”

wrote Jan van Eyck in 1434 on a mirror in the famous picture of the Arnolfini

marriage. Margrét and Stephen use mirrors first and foremost to make the viewer

into a participant in the natural process that appears in their works, make him

aware that his own presence is marked with the same uncertainty as the movement

of the waves, the bounds of sun and shadow and the whistling of the wind.

We perceive this

identification of man with nature in works such as ‘Encounters’

where Margrét and Stephen have removed part of a mirror so that the picture

does not become ‘active’ until we stand directly in front of it and perceive

our own face reflected in the remains of the mirror. ‘Portable

Sunbeams’ only requires our participation to the extent that we position

the mirrors in natural surroundings.

Most ambiguous of

all is their use of mirrors in work such as ‘Windows’,

where photographs of old windows interact, assisted by mirror coating. Here the

windows can be observed as a kind of symbol for human consciousness – in

traditional art they are used to convey the divide between an inner and an

outer world – and the work is thus a crystallization of perfect self-knowledge;

where the mind reflects nothing but itself.

Awareness of

mutability is in per se a tragic thing. We are well aware that “...before we

know it/time has tip-toed past”, to use Margrét and Stephen’s own words.

Despite this, pessimism is nowhere to be found in these monuments to mutability

that they raise in the form of photographs, mirrors, glimpses of times past

(‘The year when it snowed in July’, ‘When the frost killed the aspens’ etc.)

and exact positioning (‘Places’). Their work is

much rather characterized by the creativity and maturity of those who have

learnt to enjoy both day and moment, carrying their own ‘rays of optimism with

supporting stakes’.

Adalsteinn Ingólfsson

The following articles appeared in the Icelandic press while the ViewPoints exhibition was running:

Captivating Viewpoints and a journey for the mind

It is always fun when one is startled, stops, looks around and sees oneself in new surroundings. Not to mention if one can manage to think oneself into a whole new environment and see that environment with new and fresh eyes. That is what I experienced at Margrét and Steve's exhibition in the Kópavogur Art Gallery the other day. I wanted to take their Portable Sunbeams out of the building and see everything afresh in their mirrors. And that feeling alone completely changed my day. My mind flew to all the places I could see from new perspectives and I saw them in a fresh new light.

Margrét and Steve are known for their decades of pioneering work and optical experiments in painting, perhaps not unlike Vasarely's but with a different set of rules and quite another philosophy. In their art they have frequently played with optical deception and required a certain participation from the viewer. Their aim has been to excite the eye of the viewer with combinations of form and colour. Previously it was the painting, the object itself, that was the point of focus, but now it is the viewer and the whole environment that take pride of place. Needless to say, the quality of the workmanship in their work is admirable and this goes hand-in-hand with the thoroughly considered presentation of their ideas. The exhibition in the Kópavogur Art Gallery brightens the dark winter days. I commit these lines to paper to draw attention to the show so that others may enjoy it.

Thóra Kristjánsdóttir, Art Historian.

Concept and Design

Margrét Jóelsdóttir and Stephen Fairbairn have worked together for at least 30 years in creating works that deal with abstract optical and visually subjective values. … They use simple means to arrive at remarkable conclusions about vision and colour and the effects they produce. … Yet again (they) arrive on the scene with all manner of work that revolves around the theme of time and space as well as making use of optical solutions. Most of the couple's works sprout from amusing and almost philosophical speculations and are poetically presented.

Halldór Björn Runólfsson, Art Historian.

From our Viewpoint

The

sea has always played an important part in the way we see things. We are both

brought up close to the sea, Margrét in a small fishing town in Iceland’s

Western Fjords, and Steve in a village on the south coast of England. So it is

not surprising that we chose for our home a place with the sea on three sides.

Sleeping and waking

to the sound and smell of the sea is thus deeply etched into our consciousness.

Beachcombing expeditions are a regular part of our routine and for a place to

relax we built ourselves a summer retreat with a view over the Faxaflói bay

with the Snæfellsjökull glacier in the distance.

For a long time our work has dealt with the ever-changing, relative world in which mortals attempt to create safety and stability for themselves by organizing the erratic and manipulating the moment.

Amongst other things life entails perceiving objects and experiences from new viewpoints, finding new perspectives and new languages. To this end we exercise our curiosity - that primal childlike energy and insight. It gives us a reply to that science which tells us of the moment - how each atom is so minute that we can only sense a blur of where it might be, how truth is so remote that we can only grasp a fragment of it, how the Universe is so vast that we can only hear an echo of it. We accept our limitations and continue searching.

Margrét

Jóelsdóttir and Stephen Fairbairn

an exhibition of toys by over 120 artists from all disciplines organized by the Institute of Contemporary

Arts, in 1969. Bath Academy and several other art schools were also invited to

send in entries. Margrét had by then moved to Brighton but we continued to work

together, making use of the facilities both at Corsham and Brighton College of Art.

The two of us and another Corsham student, Peter Juerges, constructed a giant

praxinoscope, an adaptation of a Victorian optical toy in which mirrors in a revolving drum produce the illusion

of movement from a strip of images. We took this process a stage further and used the praxinoscope to blend images by

persistence of vision. This led, amongst other things, to optical colour mixing

in static images. The drum, when rotated considerably faster than was necessary

for simple movement, produced strong secondary and tertiary colours from the

flicker of light primaries (red, green, blue).

an exhibition of toys by over 120 artists from all disciplines organized by the Institute of Contemporary

Arts, in 1969. Bath Academy and several other art schools were also invited to

send in entries. Margrét had by then moved to Brighton but we continued to work

together, making use of the facilities both at Corsham and Brighton College of Art.

The two of us and another Corsham student, Peter Juerges, constructed a giant

praxinoscope, an adaptation of a Victorian optical toy in which mirrors in a revolving drum produce the illusion

of movement from a strip of images. We took this process a stage further and used the praxinoscope to blend images by

persistence of vision. This led, amongst other things, to optical colour mixing

in static images. The drum, when rotated considerably faster than was necessary

for simple movement, produced strong secondary and tertiary colours from the

flicker of light primaries (red, green, blue).

three

greyscale colour separation films and angled glass plates to produce a composite colour image. Another used a similar principle with lights

and shutters to mix the colours on painted cards and a third used polaroid sheets on revolving disks to produce colours from transparent objects. These three

boxes were shown at the Whitechapel Art Gallery at an exhibition called COLOUR?

in early 1970. Other exhibits shown there included mobile colour work by Sydney Harry and several fluorescent strobe-lit 'Videorotors' by Peter Sedgley who also knew and was influenced by Sydney. Sydney also wrote an article in the catalogue about additive and subtractive colour mixing and mobile colour.

Soon afterwards a continuation of the Whitechapel COLOUR? show opened at the Graves Art Gallery in Sheffield. This included some new work that had not been shown previously and was a huge success with over 21 thousand visitors. The Leicestershire Collection bought the 3-dimensional 'Zig-Zag Reflecting Structure' which was amongst the work that we exhibited in Sheffield.

Margrét also held an exhibition of her work at Brighton Radio and in a broadcast interview she explained how the energy of Iceland, the land, the sea, the light and the weather influenced the forms and colours of her work.

>

three

greyscale colour separation films and angled glass plates to produce a composite colour image. Another used a similar principle with lights

and shutters to mix the colours on painted cards and a third used polaroid sheets on revolving disks to produce colours from transparent objects. These three

boxes were shown at the Whitechapel Art Gallery at an exhibition called COLOUR?

in early 1970. Other exhibits shown there included mobile colour work by Sydney Harry and several fluorescent strobe-lit 'Videorotors' by Peter Sedgley who also knew and was influenced by Sydney. Sydney also wrote an article in the catalogue about additive and subtractive colour mixing and mobile colour.

Soon afterwards a continuation of the Whitechapel COLOUR? show opened at the Graves Art Gallery in Sheffield. This included some new work that had not been shown previously and was a huge success with over 21 thousand visitors. The Leicestershire Collection bought the 3-dimensional 'Zig-Zag Reflecting Structure' which was amongst the work that we exhibited in Sheffield.

Margrét also held an exhibition of her work at Brighton Radio and in a broadcast interview she explained how the energy of Iceland, the land, the sea, the light and the weather influenced the forms and colours of her work.

>

In 1976 we became members of the Finnish group, Dimensio, which

was comprised of a number of artists involved largely with optical and kinetic

work. The group held a seminar at Hässelby Slot near Stockholm and

we showed some of our work there. Peter Sedgley was also a member of Dimensio but did not take part in the Hässelby seminar. The following year Dimensio held a touring

exhibition in Finland where we showed a folding stereoscope with a series of cards which we

named ‘Stereo Portfolio’. Over the years we have done quite a lot of experimental work with stereoscopic

images, using coloured glasses, mirrors, prisms, lenses and polarizing

filters to produce spatial effects. The main problem with exhibiting this kind

of work is the considerable number of people who cannot see stereoscopic images

properly, so we have not as yet embarked on a fully-fledged stereo exhibition.

Nor does this kind of work reproduce very satisfactorily on a website, so we

hope this picture will suffice to give an idea of what the ‘Stereo Portfolio’

looks like.

In 1976 we became members of the Finnish group, Dimensio, which

was comprised of a number of artists involved largely with optical and kinetic

work. The group held a seminar at Hässelby Slot near Stockholm and

we showed some of our work there. Peter Sedgley was also a member of Dimensio but did not take part in the Hässelby seminar. The following year Dimensio held a touring

exhibition in Finland where we showed a folding stereoscope with a series of cards which we

named ‘Stereo Portfolio’. Over the years we have done quite a lot of experimental work with stereoscopic

images, using coloured glasses, mirrors, prisms, lenses and polarizing

filters to produce spatial effects. The main problem with exhibiting this kind

of work is the considerable number of people who cannot see stereoscopic images

properly, so we have not as yet embarked on a fully-fledged stereo exhibition.

Nor does this kind of work reproduce very satisfactorily on a website, so we

hope this picture will suffice to give an idea of what the ‘Stereo Portfolio’

looks like.

In late 2001 we held a big show ‘ViewPoints’ (SjónarHorn) in the Kópavogur

Art Gallery (Greater Reykjavík Area).

Here follow some excerpts from the ViewPoints catalogue which was printed in Icelandic and

English. Adalsteinn Ingólfsson helped us with the introduction. He is a art historian, critic and journalist. Educated in the UK, he has written a

number of books on Icelandic art and artists. Articles by him are frequently to

be seen in English-language publications on Iceland and he writes reviews for

the Icelandic press.

In late 2001 we held a big show ‘ViewPoints’ (SjónarHorn) in the Kópavogur

Art Gallery (Greater Reykjavík Area).

Here follow some excerpts from the ViewPoints catalogue which was printed in Icelandic and

English. Adalsteinn Ingólfsson helped us with the introduction. He is a art historian, critic and journalist. Educated in the UK, he has written a

number of books on Icelandic art and artists. Articles by him are frequently to

be seen in English-language publications on Iceland and he writes reviews for

the Icelandic press.